There’s an old saying in emergency management, “There are no

new lessons learned in emergency management, just new people learning the same

old lessons.” Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico was the 21st hurricane response in

which I had participated, the first being Hurricane Opal striking Florida in

1995.

I traveled to Puerto Rico as a part of a Red Cross

contingent mixed in on a charter flight with a Disaster Medical Assistance Team from Arizona. We

landed at a darkened San Juan Airport at 2 AM on September 23, a few days after

the storm struck the island. I was the second Red Cross person to arrive at the

federal and state operations center in the San Juan Convention Center.

|

| A much younger Michael Whitehead at the State Emergency Operations Center in Tallahassee during the Hurricane Opal response in 1995. |

|

| September 22, 2017: Red Cross volunteers and staff in Atlanta boarding a FEMA chartered flight for San Juan, Puerto Rico. |

This response was so unique and different from the others that I learned some new lessons while re-learning some of the old ones:

- There was no power, no communications, no water and no sewage almost anywhere on the Island when I arrived. In a situation where resources are in such short supply and distribution is a challenge the mass care Priority #1 is to resource the shelters. The shelters then become a Point of Distribution and the local community comes to that location to get food and water.

- “We were stuck on Day 2 of the response.” By days 3-4 in most responses power starts coming back on and the influx of outside resources catches up with demand. In PR we couldn’t get past Day 2 – the power didn’t come on and the terrible logistics of an island response kept FEMA from getting enough food and water on the island. In fact, in much of PR we are still in Day 2 of the response.

- The lack of communication was unprecedented in my experience. We had difficulty emailing or even making a cell call in the San Juan Convention Center where the Joint Field Office was established. At times, we couldn’t email or call someone on another floor or even across the room! We took pictures of each other’s pieces of paper, or their computer screen or their iPhone to capture the information that we needed.

|

| A picture that I took of a piece of paper in order to capture the addresses because our email was limited. |

- Large earthquakes like the New Madrid and San Andreas will create islands like PR, filled with millions of people unable to get power, communication, food or water. And with the bridges down, they will be unable to leave. Ironically, the many lessons learned from this response will apply to large earthquake responses.

- With populations this large (there are over 3.5 million people on the Island), we cannot bring enough shelf stable meals and bottled water on the island fast enough to meet demand, much less get it distributed in an equitable manner. We needed water purification tablets, straws and large Units capable of producing water in bulk, which is what they started bringing on the Island. Then they brought in containers for the populace to carry the water. And propane cooking stoves so that they can distribute food boxes with food that can be cooked.

- And finally, more of the responders got traumatized than in other disasters. I was.

Traumatized? Me? Yes.

I've traveled and been and seen things like this before. I was in a war zone for a year. I arrived in southern

Mississippi 3 days after Hurricane Katrina slammed into Bay St. Louis and

Waveland and Biloxi and all the other towns that were devastated. I spent 2

weeks in Manhattan after Hurricane Sandy. I've seen acres of carbonized homes

with solitary chimneys left standing in mournful protest after wildfires.

But Puerto Rico was different.

I didn’t

travel about the Island. Like during Katrina, I was working long hours so I missed all the terrible

television images that many of you saw. For 3 weeks, I sat at a table that was

one of many identical tables on the 3rd floor of the Convention Center. In the

first weeks that I was there a parade of people with problems and questions

for the Red Cross came to see me and my partner. Sometimes they were lining up

to see us. Some of these problems and questions we were able to resolve. For

most of the problems and questions we had no ready solutions nor answers.

What follows is a brief but representative collection of the

information that came to me by message, phone or in-person:

|

| The Joint Field Office on the 3rd floor of the San Juan Convention Center where I worked for 3 weeks responding to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. |

- Search and Rescue reported finding dead bodies and live people in the same house.

- A request for assistance from a nursing home, saying that they had no food or water for 2 days.

- The Puerto Rican Red Cross volunteer who burst into tears mid-sentence as she was talking to me and sobbed, “I have been trying to bring food and water to my family, but I can’t.”

- The man from Dominica who saw my Red Cross hat and stopped me as I left the Convention Center. He said that he had been living at the airport for 3 weeks trying to get home. I could see the desperation in his eyes.

- A family of tourists in a hotel who needed food for their children because they had run out of cash and no store could take a credit card.

- A family who needed a generator because their child would not survive without electricity.

- Hospitals that couldn’t get diesel for their generators because the tanker drivers were afraid of being hijacked.

- A message: “I have not heard from my elderly parents for a week. Can you tell me if they are okay?”

- A message: “My father lives alone and needs insulin. Can you help me get him a resupply?”

- An overheard conversation:

“These two elderly women live near my house. How can they

get some food and water?”

“They need to go to the point of distribution for the

municipality.”

“That’s a 30-minute walk from their house and we live on top

of a hill.”

“You need to talk to the Mayor of the municipality.”

“We never know when the distribution site will be open. And

by the time we get there everything is gone.”

“You need to talk to the Mayor of the municipality.”

“Isn’t there any other way to help these people?”

“This is the system that the Puerto Rican government has

established. Go talk to the Mayor.”

|

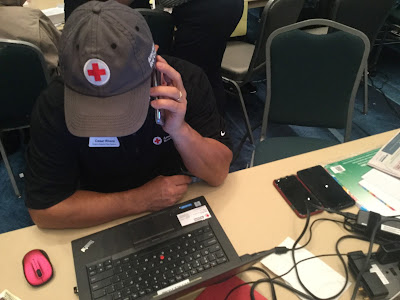

| We had lots of electronic communications devices but very little communications. |

- There was the young guy in the nice, blue U.S. Public Health Service uniform:

There were

more stories. Many more. I can’t remember them all, but I can’t seem to

forget enough. The daily onslaught of messages from desperate people who I knew

would die or suffer greatly if we could not help them, and we could not help

all of them, took an emotional toll. I didn't need to travel to the cities or the shelters to know what was going on. I had enough disaster experience to know

what the conditions were like on the island based on the reports I was seeing.

I think that I was traumatized by the fact that I traveled

to the Island to help but I found out when I got there that I was unable to

help everyone. In the other disasters I felt like we were behind but we were catching up and eventually we would get to everyone. In Puerto Rico, standing on the 3rd floor of the San Juan Convention Center, I didn't feel that way. I felt like I was in an alternate disaster universe, or in the disaster version of Groundhog Day, where we performed the same tasks with the same unsatisfying results.

I was deeply saddened by this knowledge, and still am to this day. I did the best I could. In fact, I think that I did one of the best jobs that I've ever done in any disaster. And I'm so very sorry that it wasn't enough.