It's time to move beyond Safe and Well.

Not to say that Safe and Well is broken. Safe and Well is a website where people can go to register themselves as "safe and well" or to seek out family and friends who may have been affected by a disaster. With the advent of a society where social media is widespread and even some children have smart phones, the need for sites such as Safe and Well has diminished or become unnecessary.

Unnecessary, at least, until the cell towers are down, the power is out, the smart phone batteries are dead and millions of people are seeking the status of loved ones at the same instant. Let me clarify by saying "millions of people" who are accustomed to instant communications 24/7.

When I say that we as a mass care community must move beyond Safe and Well I mean that we must prepare for situations where reunification requirements go beyond a website and involve multi-agency coordination. And for multiple agencies to be effective in coordinating during a disaster they must have a common understanding of everyone's responsibilities and the mechanisms by which they will work together toward common objectives. In other words, they need a plan.

To my knowledge. few if any county or state jurisdictions have a multi-agency reunification services plan. The State of Florida doesn't have one. Until this year, I didn't think that we needed one. And even if I thought we needed one I didn't know where to start in writing such a plan.

All of that changed more than a year ago when I was asked to join a national workgroup with the object of developing a State Multi-agency Reunification Services Plan Template. My knowledge of reunification services was pitiful but I did have a lot of experience writing mass care plans. We were fortunate to have a large number of workgroup members who had considerable disaster experience with reunification.

My participation on the workgroup (primarily twice a month conference calls) was personally and professionally rewarding. I learned a lot about reunification because I had a lot to learn and because the subject was much broader and complex that I imagined. There was a lot more to reunification that Safe and Well. Sometimes reunification comes into play when a disaster overwhelms certain local government services.

Like a lot of jurisdictions faced with mass fatality events, there were problems constructing and maintaining a missing persons list. "During the SR 530 incident the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office was not staffed to handle this mass fatality event." Local law enforcement was statutorily responsible for compiling the list but they were overwhelmed with the search and rescue effort. Multiple agencies stepped into the void to compile their own separate, uncoordinated lists. The result was that numerous families received multiple phone calls asking for information about missing loved ones. Not surprisingly, the affected families characterized this situation as "cruel."

As one can imagine, local jurisdictions must handle not only building an accurate missing persons list but dealing with the families associated with each name on the list. "The Snohomish County Health District went forward with the Medical Examiner’s Plan to establish a Family Assistance Center (FAC), without a firm understanding of the trigger points for establishing a FAC." As a result of these complications, a FAC was never established.

The point here is not to beat up on poor Snohomish County. The SR 530 Landslide was a rare and complex disaster that few jurisdictions are capable of handling. And we certainly aren't going to write a State Reunification Plan that tells counties how to handle these disasters. As we all know (and the counties keep reminding us) every county is different and every disaster is different. So what's the state concept of operations for large reunification events? We had a hard time in the workgroup coming up with an answer to that question.

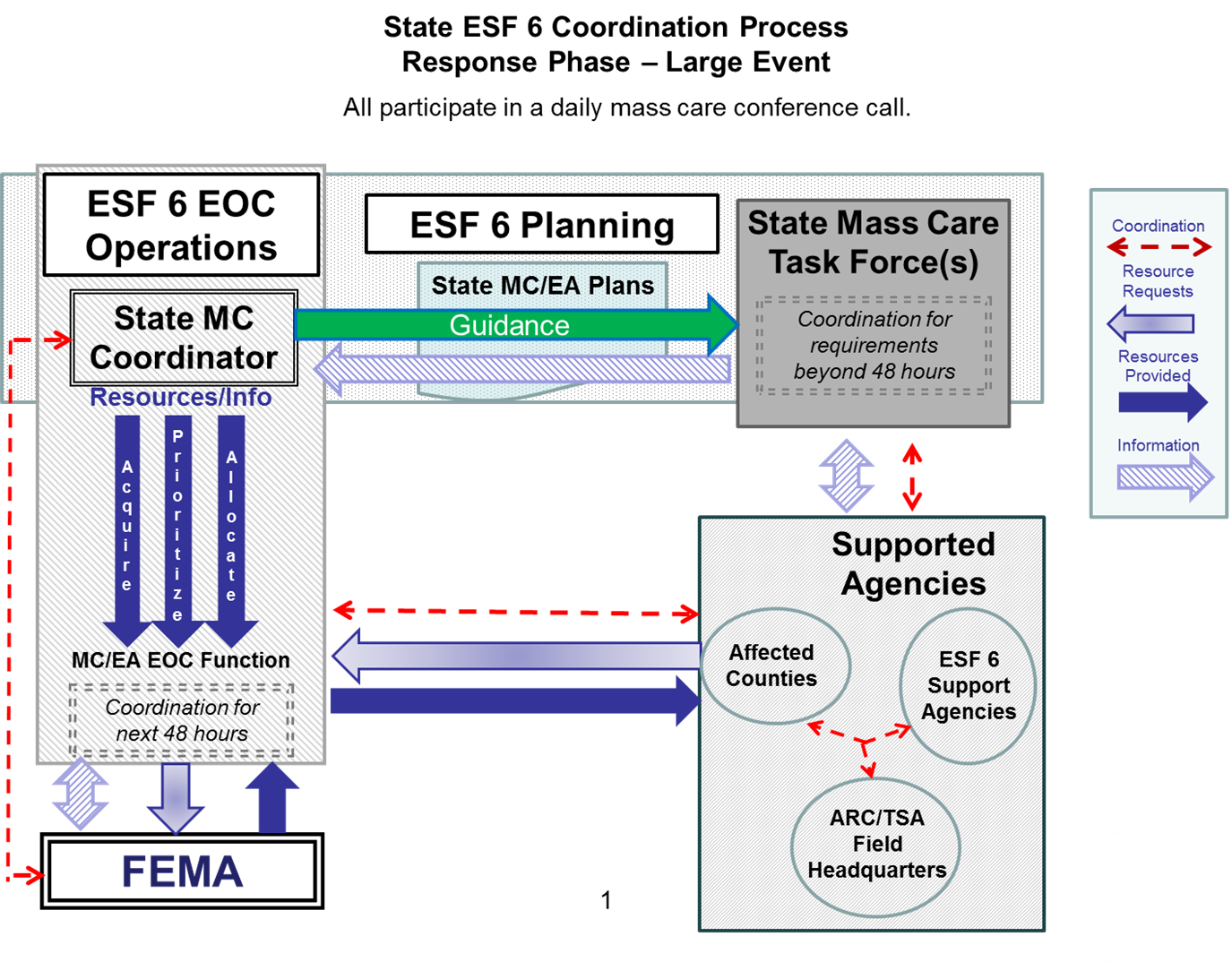

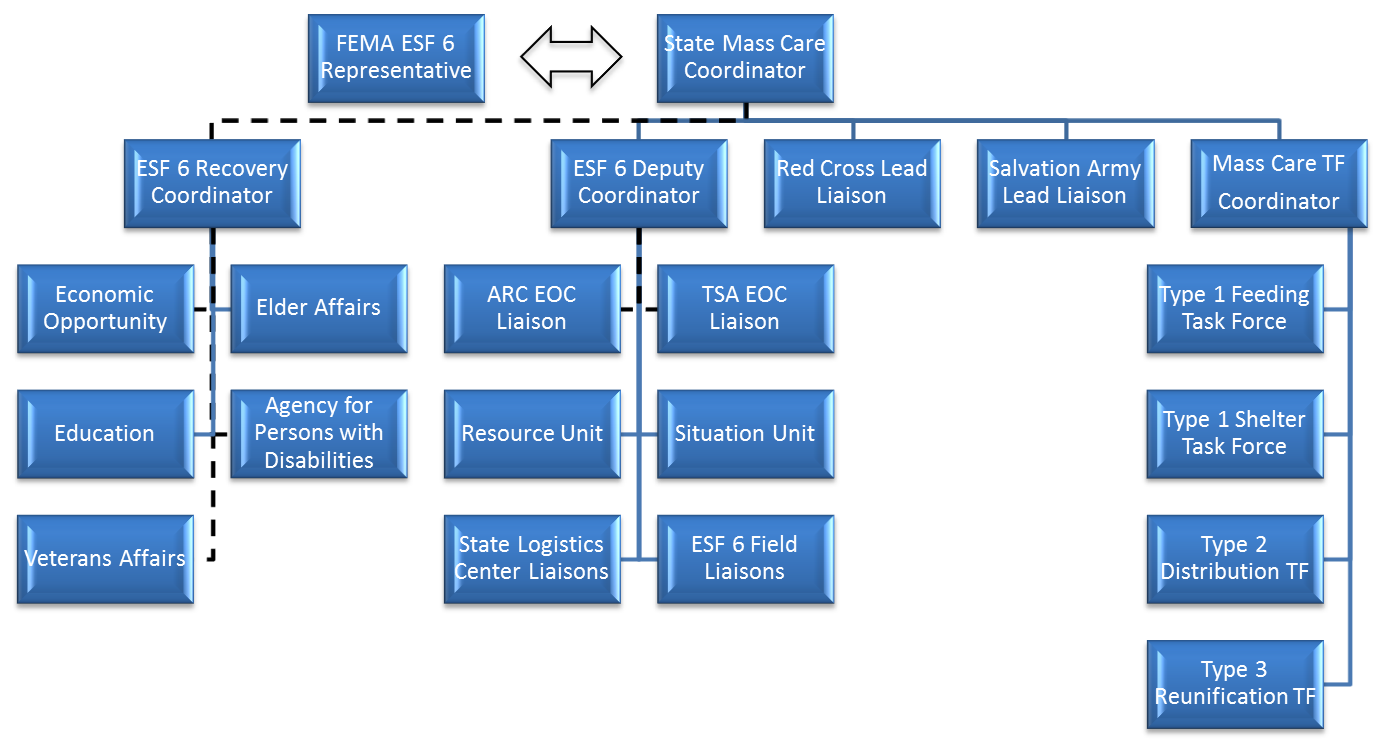

This month we finished a draft of the Template Plan and I think we came up with an answer to that question. The concept of operation is that the local jurisdiction identifies the fact that they have a significant reunification problem and, based on that assessment, requests reunification assistance from the state. Upon receipt of such a request, the State Mass Care Coordinator acts to support this request by acquiring, prioritizing and allocating reunification resources from federal, state and nongovernmental agencies.

Sounds easy, right? I believe it is. We're not going to be able to train every state and county emergency manager, much less every mass care coordinator, to handle these rare and complex reunification problems. Instead, we need to school them in Reunification Anonymous, and show them how they can recognize and admit that they have a reunification problem.

To assist local jurisdictions with this task we developed a simple and easy-to-use tool that helps them define the reunification intensity of their Event as either low, medium or high. And based on this self-assessment, they can decide if they need to ask for state assistance. The state, in turn, will use their Multi-agency Reunification Plan to bring in the necessary experts to assist with bringing reunification resources to bear in support of the requesting local jurisdiction.

In January 2015 the State of Florida will start the process to write our own State Reunification Plan. We included some counties on our planning team to keep us honest. I look forward to the experience.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)